#september 1828

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costumes Parisiens, 15 septembre 1828, (2630): Capote dont le fond est en gros de Naples et la passe en paille. Robe de cot pali brodée en lacets et garnie de volans bordés de lacets. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

'Capote', with a ball of 'gros de Naples' and a border of straw. Dress made of 'cot pali' embroidered with 'lacets' and decorated with wrinkled strips of fabric trimmed with 'lacets'. Further accessories: gloves, fan, handkerchief, ankle boots. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1820s#1828#on this day#September 15#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#Mésangère#gigot#devant et dos

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black history is not all about slave trade

Slave trade is not just black history it’s just 10% of the history africa holds

This is a message to my black brothers and sisters in America

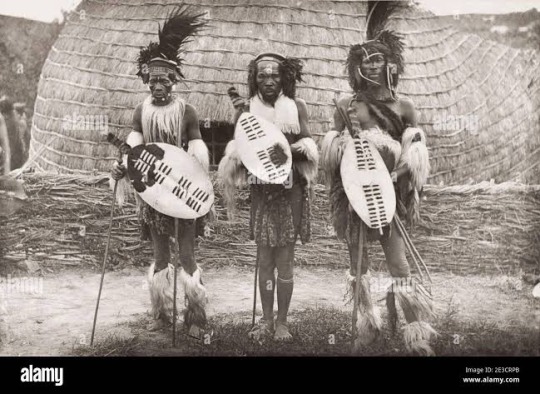

Today I will be talking about the Zulu tribe

The ancestors of the Zulu migrated from west Africa into southeastern Africa during the Bantu migrations from 2000 BC until the 15th century. The Zulu tribe expanded into a powerful kingdom, subdued surrounding groups, and settled in the region known as KwaZulu-Natal in present day South Africa. After enduring colonialism and overcoming apartheid, they have emerged as the dominant ethnic group in South Africa todayAccording to Zulu ancestral belief, the first Zulu patriarch was the son of a Nguni chief who lived in the Congo Basin of Central Africa. By the early 1800s, the Zulu had migrated to Natal, where they lived among other Nguni-speaking chiefdoms. There were ongoing power struggles among these chiefdoms.Around 1808, Chief Dingiswayo of the Nguni-speaking Mthethwa people led wars of conquest to end the power struggles among the chiefs in the communities surrounding his chiefdom.Chief Dingiswayo centralized power by organizing the military into age-based groups, rather than lineage-based regimens. This weakened kinship ties of the conquered communities. Chief Dingiswayo left the conquered chiefdoms relatively intact after they accepted his dominion.The Zulu developed into a distinct cultural group by the time they were conquered by Chief Dingiswayo and his Mthethwa people in the early 1800s. At that time, the Zulu were a small lineage numbering around 2,000 people led by Chief Senzangakhona.Shaka, the future founder of the Zulu Kingdom, was the illegitimate son of the Chief Senzangakhona. Shaka was drafted into the Mthethwa and became one of Chief Dingiswayo's bravest warriors. When Chief Senzangakhona died, Shaka seized the Zulu throne.Using Dingiswayo's military style of weakening kinship ties amongst warriors, Shaka controlled the Zulu community. After Dingiswayo's death, he killed the legitimate heir and installed a puppet as Chief of the Mthethwa.Before long, Shaka seized control over Mthethwa's regiments and assumed power of the newly formed Zulu Kingdom in 1818.

Shaka, Zulu King 1818 to 1828.

Zulu tribe facts include the following:

Shaka Day is celebrated in September by slaughtering cattle, wearing traditional clothing, and wielding traditional weapons. Dignitaries from other tribes and nations attend.

Traditionally a senior male is the head of the clan. Young men train from childhood to fight and defend the clan. Members of the clan have kinship ties based on blood or marriage.

To show respect, the Zulu do not refer to elders by their first name; they use "Baba" meaning father, and "Mama" meaning mother.

Patrilineal inheritance and polygamy are practiced in Zulu culture; having more than one wife is acceptable if one can afford it.

In Zulu culture, bride wealth must traditionally be paid in cattle. Most native groups in South Africa, including Nguni-speaking Xhosa, Ndebele, and Swazi pay bride wealth.

#life#animals#culture#black history#history#blm blacklivesmatter#heritage#africa#biden is obama's puppet#england

629 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the buildings to which Paleizenplein ("palaces square") in Brussels owes its name is the Palace of the Academies, which currently houses most of Belgium's academies.

From 1828 to 1830 it was the home of Crown Prince William of Orange-Nassau and his consort Anna Paulowna, daughter of Tsar Paul and Grand Duchess of Russia whrn Belgium (or Southern Netherlands) were part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands which was created after the battle of Waterloo in 1815. Later It was also temporarily the home of Crown Prince (of Belgium which was established in 1830) Leopold, at that time titled Duke of Brabant, to which Hertogsstraat (" Duke's street") refers. The palace is a late but pure example of neoclassicism, the palace style of the Enlightenment. This architectural gem was drawn according to pure geometric proportions, Renaissance symmetry and axiality.

The neoclassical building was built between 1823 and 1828 on the site of the Park Abbey refuge house. The state architects Charles Vander Straeten and Tieleman Franciscus Suys also carried out one of the renovations of the adjacent Royal Palace of Brussels in the same period. It was financed to the amount of 1,215,000 guilders with resources from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and on behalf of William I. The palace was furnished for his son, Crown Prince Willem and his Russian wife Anna Pavlovna. On the night of September 25 to 26, 1829, the palace was broken into. The thieves stole Anna Pavlovna's jewelry from her bedroom and escaped with it.

After the Belgian Revolution, the palace came under sequestration. An army regiment were given shelter there. It would take until 1842 before a compromise was found. The building was transferred to the Belgian state and the sumptuous contents went to the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The contents were transferred to the Kneuterdijk Palace and after the death of William II to the Noordeinde Palace, where many pieces can still be admired.

From 1848 to 1852, the palace was the location of the first regiment of Jagers-Carabiniers. King Leopold II refused to move into the building that was offered to him in 1853. It was decided to use it for ceremonies and celebrations. The interior was renovated under the supervision of architect Gustave De Man. However, in 1862 the Museum of Modern Art was housed in the palace, pending the completion and furnishing of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. It would still house works of art until the Royal Academies of Belgium were allowed to settle there (royal decree of April 30, 1876).

Interior:

In the monumental stairwell hangs a portrait of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, in honor of the original founder of the Académie Impériale et Royale des Sciences et Belles-lettres de Bruxelles in 1772. The Throne Room (not to be confused with the Belgian Throne Room in the adjacent Royal Palace of Brussels) is the original banquet room of the palace. Adjacent were the private rooms of William II, of which, among other things, the toilet with enormous wall mirror of his wife Anna Pavlovna of Russia has been preserved. The large Marble Hall on the second floor is covered with Belgian brown marble and white marble from Carrara. The parquet, constructed with oak and tropical wood (rosewood and amaranth wood), has a motif of small tree leaves. The vault is covered with gold leaf and tympanums. The hall has excellent acoustics and is regularly used for concerts. In addition, there are a number of smaller rooms, including the Maria Theresa Hall when the Academy classes meet separately, and the Leopold Hall and Albert Hall for smaller committee meetings. The old permanent secretary's office also radiates grandeur. The building also contains about sixty smaller and larger office spaces.

#neoclassical#neoclassico#neoclassicism#architectural history#architecture#historic buildings#belgium#europe#historical interior#bruxelles#brussels#brussel#bruselas#marble#gold#netherlands#palace#palaces#chandelier#lustre#history#historical#palazzo#palais#floors#parquet flooring#wood flooring#flooring

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royal Deaths, 22nd September.

1093 - Olaf III, King of Norway.

1408 - Johannes VII Palaeologus, Byzantine Emperor

1520 - Selim I, the Grim, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire.

1531 - Louise of Savoy, mother and regent for King Francis I, dies of the plague at 55.

1828 - Shaka, South African Zulu king, founder of the Zulu nation, murdered.

1840 - Princess Augusta Sophia of the United Kingdom, daughter of King George III and Queen Charlotte.

1948 - Prince Adalbert of Prussia, son of Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The original "Uncle Tom",

Rev. Josiah Henson and wife; Dresden ,Canada (c1907)

Josiah Henson (June 15, 1789 – May 5, 1883) was an author, abolitionist, and minister. Born into slavery in Charles County, Maryland, he escaped to Upper Canada (now Ontario) in 1830, and founded a settlement and laborer's school for other fugitive slaves at Dawn, near Dresden in Kent County. Henson's autobiography, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (1849), is widely believed to have inspired the character of the fugitive slave, George Harris, in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), who returned to Kentucky for his wife and escaped across the Ohio River, eventually to Canada. Following the success of Stowe's novel, Henson issued an expanded version of his memoir in 1858, Truth Stranger Than Fiction. Father Henson's Story of His Own Life (published Boston: John P. Jewett & Company, 1858). Interest in his life continued, and nearly two decades later, his life story was updated and published as Uncle Tom's Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (1876).

Josiah Henson was born on a farm near Port Tobacco in Charles County, Maryland. When he was a boy, his father was punished for standing up to a slave owner, receiving one hundred lashes and having his right ear nailed to the whipping-post, and then cut off. His father was later sold to someone in Alabama. Following his family's master's death, young Josiah was separated from his mother, brothers, and sisters.His mother pleaded with her new owner Isaac Riley, Riley agreed to buy back Henson so she could at least have her youngest child with her; on condition he would work in the fields. Riley would not regret his decision, for Henson rose in his owners' esteem, and was eventually entrusted as the supervisor of his master's farm, located in Montgomery County, Maryland (in what is now North Bethesda). In 1825, Mr. Riley fell onto economic hardship and was sued by a brother in law. Desperate, he begged Henson (with tears in his eyes) to promise to help him. Duty bound, Henson agreed. Mr. R then told him that he needed to take his 18 slaves to his brother in Kentucky by foot. They arrived in Daviess County Kentucky in the middle of April 1825 at the plantation of Mr. Amos Riley. In September 1828 Henson returned to Maryland in an attempt to buy his freedom from Issac Riley.

He tried to buy his freedom by giving his master $350 which he had saved up, and a note promising a further $100. Originally Henson only needed to pay the extra $100 by note, Mr. Riley however, added an extra zero to the paper and changed the fee to $1000. Cheated of his money, Henson returned to Kentucky and then escaped to Kent County, U.C., in 1830, after learning he might be sold again. There he founded a settlement and laborer's school for other fugitive slaves at Dawn, Upper Canada. Henson crossed into Upper Canada via the Niagara River, with his wife Nancy and their four children. Upper Canada had become a refuge for slaves from the United States after 1793, when Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe passed "An Act to prevent further introduction of Slaves, and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude within this Province". The legislation did not immediately end slavery in the colony, but it did prevent the importation of slaves, meaning that any U.S. slave who set foot in what would eventually become Ontario, was free. By the time Henson arrived, others had already made Upper Canada home, including African Loyalists from the American Revolution, and refugees from the War of 1812.

Henson first worked farms near Fort Erie, then Waterloo, moving with friends to Colchester by 1834 to set up a African settlement on rented land. Through contacts and financial assistance there, he was able to purchase 200 acres (0.81 km2) in Dawn Township, in next-door Kent County, to realize his vision of a self-sufficient community. The Dawn Settlement eventually prospered, reaching a population of 500 at its height, and exporting black walnut lumber to the United States and Britain. Henson purchased an additional 200 acres (0.81 km2) next to the Settlement, where his family lived. Henson also became an active Methodist preacher, and spoke as an abolitionist on routes between Tennessee and Ontario. He also served in the Canadian army as a military officer, having led a African militia unit in the Rebellion of 1837. Though many residents of the Dawn Settlement returned to the United States after slavery was abolished there, Henson and his wife continued to live in Dawn for the rest of their lives. Henson died at the age of 93 in Dresden, on May 5, 1883.

#Josiah Henson#Dresden#uncle tom#original uncle tom#american revolution#dawn township#kent county#methodist#preacher#tennessee#ontario#rebellion#dawn settlement#john graves simcoe#province#slaves#united states of america#united states#war of 1812#african#kemetic dreams#afrakan#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOD. Calos Salazar in Portugal cannot be stopped! The whole room is booktown central WITH....awesome lighting. Every home in America should have a dedicated library room. "All violence consists in some people forcing others, under threat of suffering or death, to do what they do not want to do." —Leo Tolstoy, 9 September 1828—20 November 1910. "Seize the moments of happiness, love and be loved! That is the only reality in the world, all else is folly." —Ibid. "People make mistakes in life through believing too much, but they have a damned dull time if they believe too little." —James Hilton, English author, 9 September 1900—20 December 1954. "A good book isn’t written. It’s rewritten." —Phyllis A. Whitney, mystery writer, 9 September 1903—8 February 2008. "You must want to enough. Enough to take all the rejections, enough to pay the price of disappointment and discouragement while you are learning. Like any other artist you must learn your craft—then you can add all the genius you like." —Ibid. "For any artistic person who creates imaginary people, the art is like inhabiting the life and mind of a seven-year-old child with imaginary friends and imaginary events and imaginary grace and imaginary tragedy." —Bob Shacochis, born 9 September 1951. “You’re a coward and a liar and a—" —Bart Sibrel, who lured astronaut Buzz Aldrin to a location on the false pretense of him doing an interview for a children's show, and then energetically denied the moon landing, interrupted when 72 year old Aldrin punched him, 9 September 2002. Listen to good music. Read great books. Keep your eyes on the sparrow.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collaborative Masterpost on Saint-Just

Primary Sources

Oeuvres complètes available online: Volume 1 and Volume 2

A few speeches

L'esprit de la révolution et de la constitution de la France (1791)

Transcription of the Fragments sur les institutions républicaines (1800) kept at the BNF by Pierre Palpant

Alain Liénard's edition and transcription of his works in Théorie politique (1976)

Some letters kept in Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan, etc. (1828)

Fragment autographe des Institutions républicaines

Une lettre autographe signée de Saint-Just, L. B. Guyton et Gillet (not his writing but still interesting)

Two files at the BNF with his writing (and other strange random stuff):

Notes et fragments autographes - NAF 24136

Fragments de manuscrits autographes, avec pièces annexes provenant de Bertrand Barère, de V. Expert et d'H. Carnot - NAF 24158

Albert Soboul's transcription of the Institutions républicaines + explanation of what's in these files at the BNF

Anne Quenneday's philological note on the manuscript by Saint Just, wrongly entitled De la Nature (NAF 12947)

Masterpost (inventory, anecdotes, etc.) - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Chronology

Chronology from Bernard Vinot's biography

Testimonies

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas on Saint-Just, as reported by David d'Angers - by frevandrest and robespapier

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas corrects Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des girondins (1847) - by anotherhumaninthisworld

Many testimonies by contemporaries (in French) on antoine-saint-just.fr

Representations

Everything Wrong with Saint-Just's Introductory Scene in La Révolution française (1989) - by frevandrest

On Saint-Just's strange representation of "throwing tantrums" - by saintjustitude and frevandrest

Saint-Just as "goth/emo boy"? - by needsmoreresearch, frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

Recommended Articles

Bernard Vinot:

"La révolution au village, avec Saint-Just, d'après le registre des délibérations communales de Blérancourt", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 335, Janvier-Mars 2004, p. 97-110

Alexis Philonenko:

"Réflexions sur Saint-Just et l'existence légendaire", Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale, 77e Année, No. 3, Juillet-Septembre 1972, p. 339-355

Miguel Abensour:

"Saint-Just, Les paradoxes de l'héroïsme révolutionnaire", Esprit, No. 147 (2), Février 1989, p. 60-81

"Saint-Just and the Problem of Heroism in the French Revolution", Social Research, Vol. 56, No. 1, "The French Revolution and the Birth of Modernity", Spring 1989, p. 187-211

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux". Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 183, Janvier-Mars 1966, p. 1-32. (première partie)

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 185, Juillet-Septembre 1966, p. 341-358 (suite et fin)

Louise Ampilova-Tuil, Catherine Gosselin et Anne Quennedey:

"La bibliothèque de Saint-Just: catalogue et essai d'interprétation critique", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 379, Janvier-mars 2015, p. 203-222

Jean-Pierre Gross:

"Saint-Just en mission. La naissance d'un mythe", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, Année 1968, no. 191 p. 27-59

Marie-Christine Bacquès:

"Le double mythe de Saint-Just à travers ses mises en scène", Siècles, no. 23, 2006, p. 9-30

Marisa Linton:

"The man of virtue: the role of antiquity in the political trajectory of L. A. Saint-Just", French History, Volume 24, Issue 3, September 2010, p. 393–419

Misc

Saint-Just in Five Sentences - by sieclesetcieux

On Saint-Just's Personality: An Introduction - by sieclesetcieux

Pictures of Saint-Just's former school, with the original gate - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Saint-Just vs Desmoulins (the letter to d'Aubigny and other details) - by frevandrest

Saint-Just's sisters - by frevandrest

On Thérèse Gellé and Henriette Le Bas - by frevandrest

Saint-Just and Gellé being godparents - by frevandrest and robespapier

On Saint-Just "stealing" and running away to Paris and the correction house - by frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

How was/is Saint-Just pronounced - Additional commentary in French by Anne Quenneday

#saint-just#antoine saint just#saint just#to be updated#masterpost#refs#sources#frev sources#testimonials and commentaries

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Metal Tube in a Polish Museum Turns Out to Be a 150-Year-Old Time Capsule

It contains rare missives from over a century ago.

For decades, a metal tube discovered on a street in Poland sat undisturbed in a museum. A recent study of the object, however, has found that it is more than a humble tube, but a time capsule containing missives from more than a century ago.

According to a press release from Poland’s Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the capsule was first discovered by archaeologists in the mid-1990s during a field study on Nożownicza Street. It remained at the Archaeological Museum in Wrocław for years until specialists from Ossolineum, a Polish cultural foundation and research center, realized there was something inside the tube and opened it.

“Inside was a manuscript signed by three Wrocław residents from Nożownicza Street, commemorating the moment of hiding this time capsule,” said Maciej Trzciński, head of the Archaeological Museum in Wrocław. “To mark this moment, they also included a copy of the 1865 Breslauer Zeitung newspaper.

Rolled up inside the tube, the handwritten note signed by three neighbors read: “On September 16, 1865, the undersigned house owners laid the cornerstone for the construction of a water tank.”

The accompanying newspaper, dated September 15, 1865, included articles discussing the political situation in Austria, the creation of workhouses for the poor, information on the stock exchange, a local theater’s repertoire, as well as announcements of engagements, weddings, and births. The daily newspaper was first published in 1820 as Neue Breslauer Zeitung before it was rebranded as Breslauer Zeitung in 1828.

According to Katarzyna Kroczak, chief conservator of collections at the Ossolineum, the process of opening the fragile artifact was a tricky one. “First, we had to disinfect the capsule and then carefully consider how to handle the delicate papers inside,” she said.

The find, the team noted, was incredibly noteworthy, as it is rare to identify individuals alongside archaeological discoveries.

“In this case, we can link the items to specific people who left behind not only this trace but also other archival records,” said Agata Macionczyk from the Wrocław museum. With this information, researchers could reconstruct the lives of the Polish residents over a century and a half later.

The discovery now serves as a reminder of Wrocław’s final renovations of its medieval water supply system. Some years after the capsule was buried, construction of a more modern water supply system to replace the medieval one began.

The time capsule and its contents are now on display at the Archaeological Museum in Wrocław.

By Adnan Qiblawi.

#A Metal Tube in a Polish Museum Turns Out to Be a 150-Year-Old Time Capsule#Nożownicza Street#Wrocław Poland#artifacts#archaeology#archeolgst#history#history news

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques Augustin Pajou - Marie Antoinette séparée de sa famille au temple - 1818

Marie Antoinette (Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France prior to the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child and youngest daughter of Empress Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis I. She became dauphine of France in May 1770 at age 14 upon her marriage to Louis-Auguste, heir apparent to the French throne. On 10 May 1774, her husband ascended the throne as Louis XVI and she became queen.

As queen, Marie Antoinette became increasingly unpopular among the people; the French libelles accused her of being profligate, promiscuous, having illegitimate children, and harboring sympathies for France's perceived enemies, including her native Austria. She was falsely accused in the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, but the accusations damaged her reputation further. During the French Revolution, she became known as Madame Déficit because the country's financial crisis was blamed on her lavish spending and her opposition to social and financial reforms proposed by Anne Robert Jacques Turgot and Jacques Necker.

Several events were linked to Marie Antoinette during the Revolution after the government placed the royal family under house arrest in the Tuileries Palace in October 1789. The June 1791 attempted flight to Varennes and her role in the War of the First Coalition were immensely damaging to her image among French citizens. On 10 August 1792, the attack on the Tuileries forced the royal family to take refuge at the Assembly, and they were imprisoned in the Temple Prison on 13 August. On 21 September 1792, the monarchy was abolished. Louis XVI was executed by guillotine on 21 January 1793. Marie Antoinette's trial began on 14 October 1793; she was convicted two days later by the Revolutionary Tribunal of high treason and executed, also by guillotine, at the Place de la Révolution.

Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou (27 August 1766, Paris - 28 November 1828, Paris) was a French painter in the Classical style.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

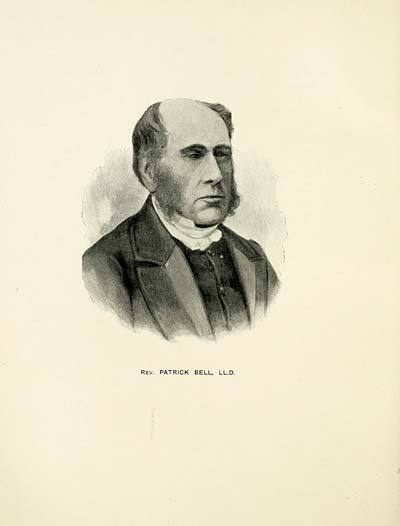

Reverend Patrick Bell was born on May 12th 1799 at Auchterhouse near Dundee.

Born into a farming family Bell was brought up at the farrm at Mid Leoch and attended Auchterhouse Parish School, Patrick Bell was only 27 when he had the idea that led to his invention, which was one of the first pieces of mechanical agricultural machinery to be used. He failed to profit financially from his invention, preferring instead to become parish minister. He studied Divinity at St Andrews University and was ordained as minister of Carmyllie Church in 1843.

Two stained glass windows at Carmyllie Church commemorate his life. He was minister in the parish from 1843 till his death in 1869.

The following excellent article is reprinted here with the kind permission of the Dundee Courier and Advertiser in 2008.

The 2008 harvest has been a trial, but spare a thought for those who had to struggle in the far off pre-combine days, when crops were cut and bound into sheaves. All highly labour intensive stuff but at least the binder could cut and bind the sheaves in one operation - before that it was sickle or scythe for cutting and hand binding.

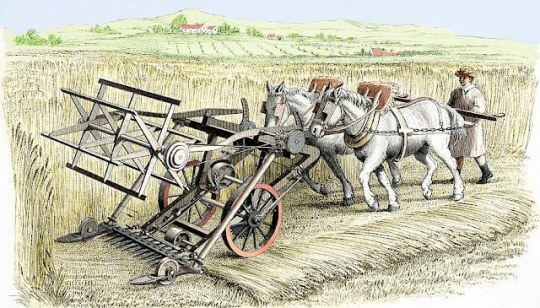

It was an Angus man who started the world's farms on the way to harvest mechanisation. Patrick Bell, a farmer's son from Mid Leoch, near Auchterhouse, developed the first successful reaper in 1828.

He had a very analytical mind and was especially interested in engineering. He installed a gas lighting system at Mid Leoch and even took an interest in the cultivation of sugar beet, growing some and extracting sugar from it a century before the industry came to Scotland.

Many people, historians included, have mistakenly credited Cyrus McCormick of America as the inventor of the reaper in 1831. However, it should be Patrick Bell who is recognised as the designer of a machine that was deemed far more efficient and reliable than any previous attempts. Four of his reapers went to America where it is likely they influenced the designs of both McCormick and his contemporary Obed Hussey.

Patrick Bell designed and built his reaper when he was a divinity student at St Andrews University, getting the idea for his cutting system from a pair of garden shears that were stuffed into a hedge. He took the shears through a gap in the hedge and tried them on some standing grain. His first design was built in model form and with the help of a Tealing carpenter a full size version was assembled. Fear of derision led him to spread earth on the floor of his shed where he planted stalks of harvested grain to trial his machine.

The reaper cut the grain adequately but it fell unevenly for gathering for hand binding. Undaunted, he developed a canvas conveyor that the cut grain fell back against. It was then transported to the side of the machine falling into a neat windrow. A revolving reel to pull the crop on to the knife was also included in his design.

Eventually satisfied with his machine's performance he and his brother took the reaper out to a field of wheat at 11pm when prying eyes were asleep. The "guid horse Jock" was yoked, but the trial started disappointingly. In their excitement the brothers had forgotten to attach the reel. They hurriedly brought it out to the field and fitted it. The machine then worked very satisfactorily. Confident of the reaper's ability a public trial was staged at Powrie Farm on the 10th of September 1828. It received a favourable report in the "Quarterly Journal of Agriculture" and received a premium of £50 from the Highland Agricultural Society, which barely covered costs.

Bell did not file for a patent believing that his invention should benefit all. This led to various copies being made that were inferior to the Bell-made machines and they did nothing to encourage wide-spread usage. However around 10 of Bell's machines were sold in east central Scotland and, as previously mentioned, four crossed the Atlantic, others went to Australia and Poland.

At this time in history labour was still cheap and many farmers did not see the benefit of such a machine, preferring to stay with traditional methods. This was another case of a good invention being too far ahead of its time. However, the Bell machine was to prove itself as far as reliability and longevity was concerned, as the original machine continued for many harvests at Mid Leoch before going to work for many more at his brother's Inchmichael Farm.

In 1852 it was put in a good state of repair and shown at the Highland Show at Perth where it was thought by many to be the latest machine on the market. However, the Americans eventually began to sell greater quantities of reaping machines no doubt due to their lightness, manoeuvrability and competitive mass-produced pricing.

Meanwhile, now ordained, the Reverend Bell became minister of Carmyllie parish where he continued an interest in engineering, working at his bench at the manse. He remained unaffected by all the clamour that his machine had caused.

The Inchmichael machine, fastidiously looked after by his brother, ended up in the Science Museum in London where it still resides today.

Two contemporary models of the machine were presented to the National Museum and one is on show at the National Museum of Rural Life at Kittochside, East Kilbride. A third was presented by his daughters to the agricultural department of Aberdeen University.

Today's combine harvester has thus developed from the work of two ingenious Scotsmen - it is a combination of Andrew Meikle's threshing mechanism and Patrick Bell's reaper.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giuseppe Donizetti — served Napoleon on Elba and accompanied him during the Hundred Days

Portrait of Giuseppe Donizetti later in life

Giuseppe Donizetti was born into poverty in 1788, in the Northern Italian city of Bergamo. The eldest of his siblings, he worked from a young age, training as a tailor’s apprentice. His true talent was in music, which was spotted early on in his life.

Giuseppe was conscripted in 1808 at the age of 20. He served the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in the Seventh Italian Regiment. He fought against Austria in the War of the 5th Coalition in 1809. He spent the years of 1811, 1812 and 1813 in Spain.

In 1811, he was became ill en route to Spain and was hospitalized at Castelnaudary in France. 43 years later in 1854, he wrote about it to the court of the Ottoman Empire:

“Constantinople, November 22, 1854. Mémoire to His Highness Achmed-Fethy Pasha. Finding myself in a comfortable position thanks to the beneficences of Our August and Glorious Sovereign, I cede to the Hospital of Castelnaudary (Aude), in which I was ill in 1811, the portion coming to me of the legacy left by the Emperor Napoleon I to the Battalion of the Island of Elba. The papers establishing my right to participate in the credit opened up by the Decree of August 5, 1854, issued at Biarritz by His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Napoleon III, I have been obliged to send to France at the time when I was honored with a brevet as Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Your Highness's Very humble Servant, Joseph Donizetti.”

Location and photograph of Castelnaudary

After the dissolution of the Kingdom of Italy and the First French Empire, he enlisted in the French military and was stationed on the island of Elba as a military flutist. It was on Elba, in the town of Portoferraio, where he was married in 1815.

That same year, he accompanied Napoleon during the Hundred Days, traveling with him on the same ship from Elba to Antibes, France. He likely fought at the battle of Waterloo.

Landing of Napoleon I in Antibes in 1815

After Napoleon:

The Austrians took control of Northern Italy after the fall of Napoleon. According to the historian Emre Aracı, Giuseppe was “a greal admirer of Napoleon and the French […] Giuseppe strongly opposed his country’s domination by the Austrians. Evidence shows that he secretly took part in the Carbonari resistance and even appeared at court trials.”

Giuseppe Donizetti became a composer, and had a full career as Instructor General of the Imperial Ottoman Music. He even composed the first National Anthem of the Ottoman Empire, the Mecidiye Marşı. His main legacy is introducing Western marching music to the military of the Ottoman Empire.

He was employed by the Ottoman government on 17 September 1828 for an annual salary of 8,000 francs. This was considered a very high salary by his family. Giuseppe’s trouble with the Austrian authorities after the fall of Napoleon may have been a motivator for him to leave Italy. He moved to Constantinople at the age of 39 and spent the rest of his life there.

Giuseppe’s patron was Sultan Mahmud II, who ruled from 1808 to 1839, and Sultan Abdulmejid I, who ruled from 1839 to 1861.

According to the historian Emre Aracı:

“The Donizettis were so well-liked in the Ottoman capital that when fire broke out near their house Ahmet Fethi Pasha, the sultan's brother-in-law, ordered all the houses surrounding the maestro's home to be razed to the ground in order to prevent the flames reaching the building.”

Sultan Mahmud II

His brother, Gaetano, called him his fratello turco— Turkish brother, writing to his friend that “He loves Constantinople, to which he owes everything.”

Giuseppe even encouraged his brother to move to Constantinople, but Gaetano declined. “I do not want to play the fool like my brother, the Bey, who, after having earned more than I perhaps, stays there in ancient Byzantium to scratch his belly between the plague and the stake,” wrote Gaetano.

Giuseppe moved to Constantinople two years after the creation of the Imperial Musical School (Muzıka-i Hümâyûn), which was an Ottoman institution which trained its students in Western style of music. He was specifically recruited as an expert to help lead this effort.

Giuseppe’s younger brother, Gaetano. By Francesco Coghetti, 1837

Gaetano Donizetti, though younger than Giuseppe, became the much more successful and internationally well-known brother, producing nearly 70 operas in his life. Gaetano is considered one of the most successful opera composers in history. Because of this, Giuseppe is widely known as Gaetano Donizetti’s brother. The historian Emre Aracı pointed out that this has actually been good for Giuseppe’s reputation because it has enabled him to be remembered when many other composers have been forgotten.

Both brothers were awarded the Ottoman Order of Nișan-i Iftihar. When Gaetano received the award at the Ottoman Embassy in Paris, he proudly said: “Napoleon belongs to two centuries, I to two religions.”

Burial:

Giuseppe died in 1856, and is buried in the vaults of St. Esprit Cathedral, on the European side of Constantinople, in the district called Pera (now called Beyoğlu). According to Emre Aracı, the district “was once the home of a thriving Christian community”. The Church was built in 1846, 10 years before Giuseppe died.

Interior of St. Esprit Cathedral

Giuseppe and his brother Gaetano are two great success stories and examples of people from impoverished backgrounds who go on to live prosperous and interesting lives.

Sources:

Herbert Weinstock, Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris and Vienna in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, 1963

Emre Aracı, Giuseppe Donizetti at the Ottoman Court: A Levantine Life, The Musical Times, Vol. 143, No. 1880 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 49-56

Emre Aracı, Giuseppe Donizetti Pasha and the Polyphonic Court Music of the Ottoman Empire, The Court Historian, Volume 7, 2 December 2002

Özgecan Karadağli, Western Performing Arts in the Late Ottoman Empire: Accommodation and Formation, 2020

#Giuseppe Donizetti#Donizetti#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Ottoman Empire#ottoman#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#gaetano donizetti#turkey#turkish history#ottoman history#first french empire#French empire#history#19th century#france#french history#the hundred days#Francesco Coghetti#Istanbul#Constantinople#1800s#19th century history#Napoleon’s soldiers#opera#composers#composer

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bellart on Herault de Sechelles

In my quest to start building some sources, I have translated Nicolas Francois Bellart's anecdote on Herault de Sechelles.

Please note:

The source for this is Oeuvres de N.-F. Bellart, procureur général à la cour royale de Paris. Tome 6, 1827-1828 authored by Billecoq. You can find the original here: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5586566r and it starts on page 124 of the text.

My French is absolute trash. And Bellart's writing does not help. @ans-treasurebox was lovely enough to help me out with a chunk of the translation and I am very grateful. However, any incorrect translation or mistake is entirely on me.

Italics are my own notes.

M. Herault de Sechelles, as everyone knows, was Advocate General in the Paris Parliament. He had wit, a lot of pretensions to the talent of speaking well, which he possessed very little of, a determined taste for metaphysics which ruined him, and above all an unbridled desire to have fame. Moreover, with everyone, and especially with the men whom he believed could serve to propagate his reputation, [he had] the most engaging manners, gentle forms and treated those around him with flattering equality to bolster their self-esteem.

Young lawyers, principally, were the objects of his coquetry. He spied on their forces, and when he thought he had discovered that a beginner was worth winning over, he had no rest until he had attached him to his chariot by his attentions and courtesies.

And to deserve his attention it was not necessary to have brilliant faculties; it was enough to be someone ordinary. I was precisely one of those men. So, I had my turn of seduction with M. Herault de Sechelles. He sought me out, made many advances to me, even coming to see me in a poor little apartment which I occupied at a cork maker. There was indeed, in these kindnesses of a great magistrate, for a poor little lawyer, the son of an artisan, enough to turn my head. So, he turned me around: and frankly, I began to love M. Herault with all my heart, to recommend him, to praise him, to celebrate, in short, as best I could, his fine and good qualities.

He undoubtedly learned about it. He was very grateful to me: and to add to my enthusiasm by his good graces, he invited me with M. Pigeau, then his secretary at the Palace, to go and spend a few days of the holidays at his chateau at Epone*

*Bellart writes Éponne here.

One can judge the eagerness with which I accepted. On one of the first days of September, I therefore went there. I found there, besides the master of the house, a certain Y.....,* his private secretary (1), brother of the conventional of that name; M. de La Salle, the most obscure metaphysician of his time, author of the Desordre Regulier, and finally Vitry, prosecutor in parliament. The revolution had begun. I noticed it in the evening.

*I’m not sure who this is referring to.

(1) The man of whom Bellart spoke here has been, for some years now, by his humility, by his piety, by the practice of all Christian works, the model of the most sincere conversion. Bellart most likely ignored it, since he didn’t comment on it, but I, who know who this man is, I had to say it. (Author's Note) [Billecoq].

And at supper and after supper the most extraordinary theses were raised. We were discussing them three against three, M. Pigeau, Vitry and myself on one side, M. Herault, Y..... and de La Salle on the other. I heard proposals to make my hair stand on end. God, religion, even the respect due to paternity, everything was called into question, and with a cynicism and freedom of expression that made me wonder more than once if I was not dreaming and if I was really with one of the first magistrates of France. M. Pigeau and I, when we retired to our rooms in the evening, we moaned, about everything we had heard, blaming on Y .... and de La Salle all the odious doctrines that the ease of character of M. Herault had made him welcome. For me, in my real tenderness for the latter, I was truly distressed.

An incident happened the next day to divert me a little from my sad thoughts. Very early in the morning, the famous president of Saint-Fargeau [Lepeletier] arrived at M. Herault's, to whom he told, as he got out of the carriage, that he had spared himself a week to spend it with him. The master received this new guest wonderfully, and the two of them, with M. Pigeau and myself, went for a walk in the park while waiting for lunch. I don't know how it happened that we got together two by two. [Lepeletier] took possession of M. Pigeau for a few moments; I stayed with M. Herault. When we were a little apart from each other:

"You heard,” said M. Herault to me, “[Lepeletier] telling me that he was coming to spend a week here. He won't even stay for dinner.”

“- How! Why?”

“I don't want to tell you that. You'll find out later. But you'll see if I'm prophesying correctly."

He didn't want to go into more explanations then. Soon the lunch bell rang. Everyone from the night before gathered to meet the newcomer in the dining room. He looked rather distant, said little, and went out for a few moments towards the end of lunch, then returned to his place at the table. We chatted; half an hour passed. [Lepeletier]'s valet brought letters to his master, who, to read them, retired to an opening in the window.

Soon he returned to M. Herault, to whom he declared, with great appearances of contradiction, that he was in despair, but that it was necessary to get him post horses without delay, since a matter of the greatest emergency recalled him immediately to Paris. M. Herault seemed to take this speech at face value. The horses came. [Lepeletier] left. When the carriage which carried him left the yard, M. Herault burst out laughing, saying to me:

“Well! Will you now believe my prophecies?” I asked him for the key to the enigma.

“The key to the enigma,” he replied, “is Vitry. "

Everything was explained. Vitry was a prosecutor in parliament. [Lepeletier], such a great zealot of liberty and equality, was the most arrogant man who existed. He considered it a diminution of dignity to go down to dinner with a prosecutor. The prosecutor had put him to flight. This is where this execrable demagogue was then in his republicanism, he who voted for the death of his master.

Rid of him, M. Herault and his guests returned to their ease. Metaphysical controversies resumed. In this cursed castle we only discussed, and God knows what we discussed! The master of the house rested from impieties with obscenities. Finally, in two or three days, I discovered that he was materialistic to the highest degree. My sorrows came back to me. I was losing respect for the master. I couldn't stop myself from retaining my affection for him. I set out to convert him. I clung to him. Several times, tete a tete, while out walking, I employed all my wisdom to combat his deplorable doctrines. I spoke to him with force, with warmth, with interest.

"What a disheartening belief," I said to him one day, grasping his hands warmly, "to have in this world neither the interest to do good, nor a witness to the good one does, nor a goal toward which one strives while doing it. Religious beliefs, the desire to please God through love and charity towards others, the hope of being rewarded by being kind and obliging to others, even at one's own expense, are the foundations of benevolence, friendship, and generosity. In materialism, the universe is empty. Morality is even emptier. There remains no longer a single reason not to sacrifice others to a harsh and cruel selfishness."

As I was uttering these words with great heartfelt enthusiasm, my interlocutor could only discern one notion from it, namely that I feared his opinions might make his willingness to assist me grow colder; thus, seemingly, I was engaging in a dispute with him only for the sake of the safeguarding of his favor that I wished to maintain!

"Don't be afraid," he said to me in a tone that brought tears to my eyes, "even though I am a materialist, I will still take care to serve you if necessary." Ah !

“Advocate General,” I cried to him bitterly, “you are cruelly mistaken, it was not about me: it was only about you, but since we understand each other so little, let's talk about something else. " And we talked about something else. Indeed, this sordid suspicion, thrown on an outpouring of heart which would have made me at that moment almost sacrifice my life to pass into his soul, for his happiness, all the convictions which burned in mine, had the effect on me of icy water falling on hot coals.

I made up my mind from that moment to make a short stay at E, where disgust pursued me all the more invincibly because my friendship, mingled with gratitude for the master, had at first been more exalted, and because the hope of seeing him return to reason and happiness had just died. A discovery which I made two days later made me make up my mind in a hasty manner.*

*I can't believe Bellart doesn't tell us what he saw.

I left the next day. I never saw M. Herault again in my life.

I don't see him again at his house, at least. I contented myself with writing to his door at the times of the year when I could not have omitted this homage without exposing myself to the danger, either of appearing insolent, or of explaining my conduct. I saw him again sometimes, but in public, at the prosecutor's office, where the lawyers used to go before the hearing. I saw him there again to confirm myself in the estrangement which he inspired in me, and to which he added considerably by a story which I heard him tell one day. It was some time after the storming of the Bastille. The unfortunate Berthier had been massacred by the revolutionary cannibals, who paraded his sad remains in the capital. His head, carried on the end of a pike, had reached the top of the Faubourg Saint-Martin. However, M. Foulon, father-in-law of the victim, arrived at the same place, dragged in a cabriolet from which the imperial had been torn off, by another troop of scoundrels, who also demanded with loud cries that they hang him from a lantern. The two bands met. The monster who bore Berthier's head had the ferocity to bring it closer to Foulon's and to force this poor old man, half dead, to kiss it.

It was precisely this execrable adventure that M. Herault related. He told it with a kind of naturalness and lightness that made me shiver. He told it almost pleasantly, and as if he had told something that would have been nothing but ridiculous. And when he came to the atrocious act of having wanted the unfortunate father-in-law to lay his lips on this head separated from the trunk of his own son-in-law, he smiled, saying "Just imagine this scene, and this bastard presenting his head to the father-in-law, as if he had said to the son-in-law, kiss dad, kiss dad."* These words froze me. I didn't want to hear any more coming out of that coldly cruel mouth. Never have I seen him since.

*The actual French here has him saying, “Baise papa, Bais papa". You may translate that as you wish.

This man was not a barbarian; he was not even revolutionary. He was so little [a revolutionary] that, when asked which political party he was from, he answered: “the one that doesn’t give a fuck about the two others.” And it was true. He was selfish; he was a philosopher; he was materialistic. He wanted to escape, to live, to live like animals. He was neither good nor bad. He possessed neither virtues nor vices, at least not the kind that harm others; and with all that, either through absolute carelessness, the primary trait of that base soul, or through complete indifference to good and evil, or, finally, due to a crude desire for his own survival, he complied with whatever was desired, took part in crimes, and voted for the death of his king, and perished on a scaffold, in the midst of brigands whom he had made his fellows, his companions and his friends. I dwelt on this man, because I recently read his eulogy, and I felt indignant.

#herault de sechelles#frev#qui posts#tumblr is being an idiot with the formatting - Ill deal with it later

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Among the Russian tsars, I find Alexander II the most handsome, his father Nicholas I and his grandson Nicholas II. But Alexander II has always been my favorite because of his looks that remind me of a kitten. I would like to ask you, could you please tell me about Alexander II's physical characteristics? He looks very cute even as a child, and we should not be surprised that when he became a grown man, many women, like Queen Victoria, admired him. What was his appearance like, did he find himself handsome? Did his parents think he was handsome? Thank you a thousand times in advance for your answer 🤗💗

I can offer you a few quotes on the young Alexander II’s physical appearance from his grandmother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, and from his father, Emperor Nicholas I, but as far as I can tell, most often, people remarked on his good nature rather than on his looks. But yes, he was supposed to have been relatively handsome. That was the general consensus regarding most of the Romanov men.

From Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna:

“He is a charming child, well endowed by nature, who gives us great hope for the future.” - 20 June 1827

“Sasha is as agile as a little monkey.” - 22 July 1827

“Young Alexander is the most remarkable child.” - 14 September 1827

From Emperor Nicholas I:

“…my eldest, growing a lot, has an angelic soul and is a perfect good devil… he resembles our late Angel [Emperor Alexander I] a great deal.” - 16 February 1828

“Sasha is approaching my height.” - 3/15 February 1837

“Alexander has grown a moustache.” - 1/13 November 1835

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

" Residential Schools were a Canadian institution established by the government with the goal of assimilating Indigenous children with into Euro-Canadian culture. They operated from 1828 until 1996/7, spanning all the way across Canada. These school were often the site of all types of abuse abuse, neglect, cultural erasure, and often death."

" Most Indigenous people today are descendants of these survivors, or survivors themselves. I myself am the second generation not to attend residential school. For many Indigenous communities, the effects of intergenerational trauma from residential schools continue impacting our daily lives today. The journey towards healing is complex and deeply personal."

~~~~~~~~~~

" Orange Shirt Day, observed on September 30th every year. It is also known as National Day of Truth and Reconciliation. It is a day of remembrance and commemoration for the survivors of residential schools. It serves as a poignant reminder of the impact of residential school and the resilience of our peoples."

" In the wake of the profound trauma of being a child of residential school survivors, many Indigenous people are moving towards reconnection, healing, and cultural revitalization. Indigenous communities are reclaiming and celebrating our culture, traditions, languages and ceremonies."

#indigenous#ndn#native american#residential school#orange shirt day#every child matters#residential school survivors#indian day school#canada#canadian history#ndn tag#ndn tumblr

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Józef Poniatowski’s children and descendants

Because a couple of months ago there’s been a discussion about Napoleon marshal’s children I decided I out to share with you the info about Józef Poniatowski’s issues and descendance.

Though never married, prince Józef nevertheless had two illegitimate sons.

The oldest one was Józef Szczęsny Mauricy Chmielnicki, born on the 17th of September, 1791.

The mother of the boy was most probably Poniatowski’s mistress of that time, the actress named Małgorzata Magdalena Wiktoria “Zelia” Sitańska (though there are as well versions it might have been another woman, for example, Zelia’s step-mother, also an actress - more on the topic I wrote here)

Zelia and here step-mother, a colored engraving

As for the fate of the boy - in his youth (before 1807) he started a military career in the Army of... Austria. Most probably it was prince Józef himself who arranged it, because his career started in the Austrian army too. (Another question is why Poniatowski didn’t “transfer” his son into the Army of the Duchy of Warsaw after the latter had been created, but, I’m afraid, we’ll never know the answer.)

And when in 1809 Austria attacked the freshly created Duchy, Józef Chmielnicki took part in the war... on the side of the Austrians. (And his father kinda accepted this, because in his will written 3 years later, in 1812, Poniatowski mentioned not only his firstborn but as well the fact that the latter was an officer in the Austrian Army.)

Chmielnicki fought as well in the next coalition wars, in 1812-1815 (against Napoleon as well), in 1831 he fought in defense of the Roman ecclesiastical state against local insurgents; for this he received the papal Order of St. Gregory. He also had the Austrian Military Cross. In 1856 he retired with the rank of colonel. He died unmarried in Vienna in 1860.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find any image of Józef Chmielnicki, but in his military service records there is a little bit on his appearance:

Tall, of good health, very lively temperament and honest and reliable character. Polite and tidy; sometimes a bit violent and not always consistent. Zealous and active, with a special penchant for service in rifle units. He was wounded twice. He is fluent in German and Polish in speech and writing, speaks French and a little Italian. A very good staff officer, suitable for a regiment commander.

More do we know about Prince’s Józef’s other son, who was born on the 18th of December, 1809 in Warsaw and was then was given the name Józef Karol Ponitycki.

Józef Peszka, Portrait of Józef Ponitycki, 1815

As for Józef the second mother - there are no doubts in it, it was prince Poniatowski’s another mistress, Zofia Czosnowska née Potocka (more about her - here).

Though Czosnowska was married, prince Józef acknowledged her child and mentioned him in his will.

A miniature showing Ponitycki at the age of ten

The boy’s mother, however, didn’t care for her child much. Having divorced her official husband she married again in 1815, then placed her son in the custody of his aunt, prince’s Józef sister countess Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz.

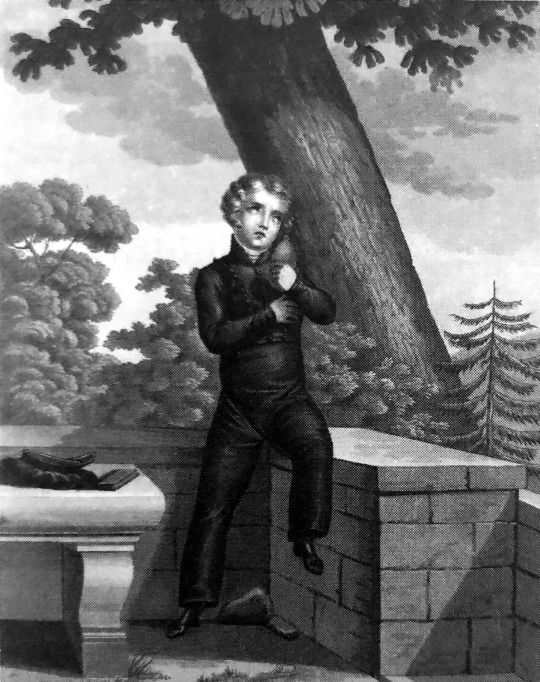

In the 1821 countess Teresa became the boy's legal guardian (Czosnowska officially gave him up) and in 1828 adopted him, changing his surname from Ponitycki to Poniatowski and adding Maurycy (Maurice) as his third name, thus making the boy the namesake of her long-term love Charles Maurice de Talleyrand.

And a little bit before, in 1826, Józef the younger gained French citizenship, and at the age of 18 (1827) he volunteered to join the French army.

An anonymous painter, Prince Józef's son grieving after his father, 1820

The enlistment papers say that he was a healthy, blue-eyed, tall (1.79 m) blond, oval face, strong chin and aquiline nose. After graduating from school, he took part (as chasseur sergeant) in the Greek campaign in the Peloponnese (1829), later he was transferred to Algiers (1830), but he quickly returned to France.

During the July Revolution in Paris that year Poniatowski was among those soldiers who were putting it down, but when a year later the November Insurrection broke out in Poland he, together with his friend, Count of Montebello, a son of the Marshal Lannes, went to Poland to join the uprising. After the fall of the uprising, Józef returned through Galicia to France, where joined the rifle regiment as a captain and took part in the war in Algiers with Abd del-Kader in the years 1832-1836.

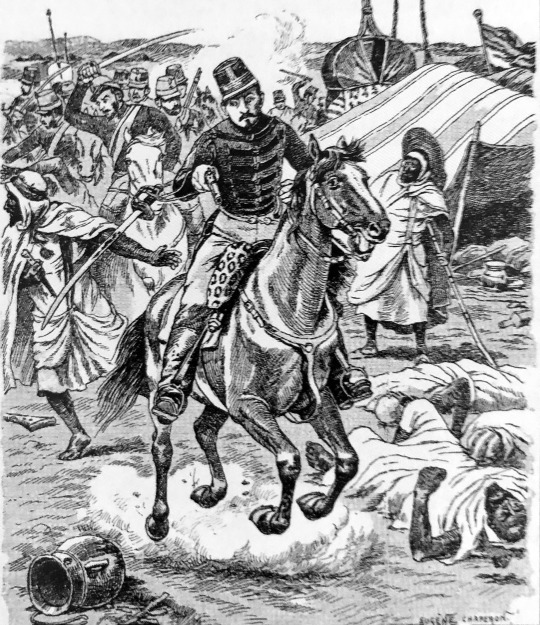

Józef Ponitycki-Poniatowski charges the camp of Emir Adb-el-Kader, a drawing by a French painter Eugène Chaperon

In 1839, driven by longing for his homeland, Poniatowski came to Kraków and made efforts to obtain permission to return to Warsaw. But the Russian Governor Paskevich refused him entrance and even tried (unsuccessfully) to confiscate) properties Józef inherited from his father and aunt.

Not being allowed to return to Poland, Poniatowski returned to France and to his regiment. He died on February 15, 1855 in Tlemcen, Algeria, and was buried there.

As for Józef Karol Poniatowski’s private life - in 1836 he married an Englishwoman, Maria Anna Semple. They have two children - a son, Józef Stanisław, born in 1837, and a daughter, Maria Teresa, a year younger.

Józef Stanisław joined the army at the age of 17 and went on the Crimean campaign. During the siege of Sevastopol, he was appointed lieutenant for his bravery. He then served in the cavalry regiment. He left the service due to ill health. In 1866 he married Léonide Marie Victoria Charner, the daughter of a French admiral, the chief commander of a sea expedition to China.

Six weeks after his marriage with Léonide Charner in 1866 he became mental ill. From 1880 until his death July 20, 1910 in Geel, Belgium, where he resided as a psychiatric patient in the wellknown Geel "Colonie des Aliénés''. (Many thanks to Werner for providing me with this information).

As for Józef Stanisław’s issue - there we have a kind of discrepancy. According the Polish sources like, for example, the Genealogy of the Descendants of the Great Sejm , he died childless but according his profile at geni.com he did have a son, named André whose descendants still live in the US. (The site doesn’t allow to see all the data but it is highly probably that the direct male line continues till our days.)

Maria Teresa, after the death of her father, was taken care of by the Duchess d'Eckmühl, the widow of the Marshal Davout. In 1859, Maria Teresa married Louis de Guirard, Comte de Montarnal, grandson of Marshal Ney. He was an official in the Ministry of Treasury. They had seven children: three sons and four daughters. But neither of those, according both the Genealogy of the Descendants of the Great Sejm and Geni.com had issue.

What’s more, according Geni.com Józef Karol Poniatowski after the death of his first wife married again. That time he took as a wife a woman named Elżbieta Fuchs, and they have a son named Wojciech Józef. That Józef, it looks like, was married, but no information about his issue is provided.

#Poniatowski#józef poniatowski#zelia sitańska#Józef Szczęsny Mauricy Chmielnicki#zofia czosnowska#Józef ponitycki#józef karol maurycy poniatowski#józef poniatowski's children#józef poniatowski's descendants#józef peszka#eugène chaperon

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solange Dudevant (13 September 1828 – 17 March 1899) was a French writer and novelist and the daughter of George Sand | Portrait de Solange Dudevant by her husband Auguste Clésinger via Wikipedia

2 notes

·

View notes